By Sister Mary Jo Curtsinger

Mid-July presented us with two kinds of scorching heat that made it hard to breathe; one reported by the weather channel and the other by political newscasts. At the same time, the lectionary presented us with the Gospel of the Good Samaritan from Luke:

On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

“What is written in the Law?” Jesus replied. “How do you read it?”

He answered, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and, love your neighbor as yourself.”

“You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.”

We know this story pretty well, right? The scholar questioned Jesus, yet then answered his own question correctly in describing the heart of revelation as loving God with one’s whole self, and loving the neighbor as oneself. But the scholar couldn’t stop there and asked Jesus this follow-up:

And who is my neighbor?

Imagine a mixed crowd of people in the United States today, listening closely to Jesus’s response to try to catch a political spin. Would his answer to the question be:

“Your neighbors are the migrant peoples desperately running for their lives from their violent homelands…”

Or, maybe they’d be listening for a lead-off reply like:

“Your neighbors are the innocent unborn children in this country, in mortal danger of ever drawing their first breath…”

With either answer, Jesus would lose half the crowd. Today we live in the land of sound bites and snap judgments, rarely waiting for what follows a comma.

But Jesus answered, as he often did, with a story or parable of people who found themselves traveling the same road. One of these people shows us what it looks like when someone lives wholly in love with God, whose nickname is Compassion.

I checked out what eminent scripture scholar Father Raymond Brown (d. 1998) had to say about this parable in his book An Introduction to the New Testament.

Fr. Brown wrote that Jesus’s answer—that is, his telling the story of the Compassionate One on the road—illustrates Jesus’s point that, one can only define the subject of love, not the object.

That is, one can only define the lover, not the ones who are to be loved. Jesus chose a Samaritan to illustrate a person, a subject, whose range of loving is unlimited. So, Jesus is telling us that asking, “who is my neighbor?” is the wrong question. The better one is, “who am I, and who do I want to be?”

Thank you, Fr. Brown.

Let’s take a look at a few more people who have meditated on this story. Consider this artistic interpretation of the parable by 17th century Italian painter Domenico Fetti (d. 1623).

Apparently, Domenico doesn’t want us to spend too much energy on the two figures receding in the lower left corner of the painting – the priest and  the Levite who hurried past. Luke doesn’t actually tell us why, but as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once observed, the ones who hurried away may have asked themselves, “If I help this person, what will happen to me?”

the Levite who hurried past. Luke doesn’t actually tell us why, but as Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. once observed, the ones who hurried away may have asked themselves, “If I help this person, what will happen to me?”

In Jesus’s parable, the compassionate Samaritan asked, “If I don’t help this person, what will happen to him?”

Clearly the Samaritan and the object of his mercy are front and center. Domenico seems to want us to look into the eyes of the one who has been saved from the ditch, because it is his eyes we can see. The face of the merciful helper is not revealed.

Where is the rescued person’s gaze at the moment he’s hoisted to safety? At first I thought he was looking straight at me, trying to catch my eye. But then I wasn’t sure…maybe his gaze is unfocused, sort of lost in utter amazement that he was suddenly given hope again, and surprised that his life has been given back to him.

Where is the rescued person’s gaze at the moment he’s hoisted to safety? At first I thought he was looking straight at me, trying to catch my eye. But then I wasn’t sure…maybe his gaze is unfocused, sort of lost in utter amazement that he was suddenly given hope again, and surprised that his life has been given back to him.

Can we dare to put ourselves in the place of this vulnerable one? To realize that we too are this vulnerable when alone, and to feel the wonder and gratitude of, “…I once was lost but now am found”?

What about the figure of the Samaritan, whose face we cannot see? We know that the hearers of Jesus parable looked down their noses at Samaritans; they were traitors, hated foreigners, enemies.

But Jesus’s listeners didn’t really know any Samaritans personally. They would hardly let their eyes meet those of Samaritans, much less ask the 1st century equivalent of, “How’s it going?”

Let’s hear from Dr. Amy Jill Levine, a Jewish scholar of the New Testament. She notes in her book, Short Stories by Jesus, that, not only does the Samaritan feel the pain of the wounded one in his gut (compassion), he allows himself to be inconvenienced by time-consuming, resource-depleting action. That is, he showed mercy.

Let’s hear from Dr. Amy Jill Levine, a Jewish scholar of the New Testament. She notes in her book, Short Stories by Jesus, that, not only does the Samaritan feel the pain of the wounded one in his gut (compassion), he allows himself to be inconvenienced by time-consuming, resource-depleting action. That is, he showed mercy.

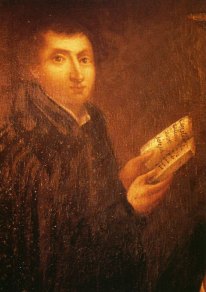

I turn to a final interpreter of this Christian tradition, to the Jesuit priest who was living in neighboring France during part of Domenico’s day. He is none other than the one who co-founded the Sisters of St. Joseph (along with our first 6 sisters) in 1650, Fr. Jean Pierre Médaille.

Fr. Jean Pierre reiterated Jesus’ teaching that we are to love God and neighbor without distinction. If you’ve heard this before, what is your understanding of it? That when you’re loving your neighbor, you’re loving God?

Fr. Jean Pierre reiterated Jesus’ teaching that we are to love God and neighbor without distinction. If you’ve heard this before, what is your understanding of it? That when you’re loving your neighbor, you’re loving God?

Or,

That you are to love all neighbors as you love God without distinction? That every neighbor, every person, is to be loved as much as any other neighbor or person?

Fr. Médaille headed off the red herring-question of, “Who is my neighbor?” by his choice of words. In his original French, he referred to the neighbor as la prochaine, which means “the next one.” That is, the neighbor is the next one you encounter, or the one who is right next to you.

Consider one of Fr. Médaille’s maxims, one that reflects Jesus’s teaching on compassion: “Interpret another person’s actions in the best possible light.” Many of us sisters would tell you, it’s one of the most challenging to heed in everyday life.

Sisters and associates of St. Joseph have inherited the Ignatian spirituality of being “contemplatives in action.” The scholar in Luke’s gospel seemed to get it: that compassion (a feeling) and mercy (an action) are Jesus’s teaching. And so, that’s our call: to open ourselves to feel the gut-wrenching needs of the ones we encounter, and to act with mercy in response.

But where to start? With whom? How?

God revealed the answer in Deuteronomy (30:10-14) which tells us to fear not, the command is not too mysterious or remote for you. The Word of life is something very near to you, already in your mouths and in your hearts, you have only to carry it out.

When we need help, we look to God whose range of loving is unlimited. The Spirit gathers us at Eucharist and elsewhere to remember and know the One who lifts us up and pours the wine of compassion over our wounded hearts, and anoints us with the oil of mercy… so that we might go and do likewise.

About the Author

Sister Mary Jo Curtsinger, CSJ, holds a Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree from Catholic Theological Union (CTU) in Chicago where she later served as the director of the Biblical Study and Travel Program. She was received as a candidate for vowed membership with the Congregation of St. Joseph in 2002 and professed final vows in 2011. She taught theology courses at Nazareth Academy in La Grange Park (a sponsored ministry of the Congregation), and now serves as Co-Director of Vocations Ministry for the Congregation.

Sister Chris Schenk has worked as a nurse midwife to low-income families, a community organizer, a writer, and the founding director of an international church reform organization, FutureChurch. Currently she writes an award-winning column “Simply Spirit” for the National Catholic Reporter.

Sister Chris Schenk has worked as a nurse midwife to low-income families, a community organizer, a writer, and the founding director of an international church reform organization, FutureChurch. Currently she writes an award-winning column “Simply Spirit” for the National Catholic Reporter.

Sister Ann Letourneau, PsyD has been a Sister of St. Joseph for 29 years. She is a staff psychologist at Central Dupage Pastoral Counseling Center in Carol Stream, IL where she sees individual clients and offers educational presentations on various psychological and spiritual topics. Sister Ann is fascinated by nighttime dreams and runs a monthly dream group at

Sister Ann Letourneau, PsyD has been a Sister of St. Joseph for 29 years. She is a staff psychologist at Central Dupage Pastoral Counseling Center in Carol Stream, IL where she sees individual clients and offers educational presentations on various psychological and spiritual topics. Sister Ann is fascinated by nighttime dreams and runs a monthly dream group at

Sister Carol Crepeau, CSJ, ministers as a facilitator and leader of group dynamics for non-profits. Guiding the annual Congregation of St Joseph Pilgrimage to LePuy and Lyon, France is one of the most wonderful activities of her life. She also enjoys a good book and gathering with friends for prayer and conversation.

Sister Carol Crepeau, CSJ, ministers as a facilitator and leader of group dynamics for non-profits. Guiding the annual Congregation of St Joseph Pilgrimage to LePuy and Lyon, France is one of the most wonderful activities of her life. She also enjoys a good book and gathering with friends for prayer and conversation.

Elizabeth Powers is the Electronic Communications Manager for the Congregation of St. Joseph and manages the blog, Beyond the Habit. She sometimes acts as a contributing writer. She loves reading, writing, and Harry Potter. She is a new mom, and working to figure it out!

Elizabeth Powers is the Electronic Communications Manager for the Congregation of St. Joseph and manages the blog, Beyond the Habit. She sometimes acts as a contributing writer. She loves reading, writing, and Harry Potter. She is a new mom, and working to figure it out!

At that meeting, one of the Sisters who had been an educator her whole life spoke about having taught students to be law abiding; she just couldn’t agree to “break the law.” In response, I questioned whether God’s law didn’t take priority. It was a conundrum, and we face the same conundrum when we seek to exercise our moral authority in other matters. I’d like to pose the following question to each of you: What do you consider to be your moral authority and responsibility?

At that meeting, one of the Sisters who had been an educator her whole life spoke about having taught students to be law abiding; she just couldn’t agree to “break the law.” In response, I questioned whether God’s law didn’t take priority. It was a conundrum, and we face the same conundrum when we seek to exercise our moral authority in other matters. I’d like to pose the following question to each of you: What do you consider to be your moral authority and responsibility? For some, one’s moral responsibility is simply keeping the civil law. The assumption is that civil law is right and just. Sadly, that is not always the case. The group of people who are most concerned with keeping the civil law might also be concerned with the consequences of breaking it—having to pay a fine or to spend time in jail.

For some, one’s moral responsibility is simply keeping the civil law. The assumption is that civil law is right and just. Sadly, that is not always the case. The group of people who are most concerned with keeping the civil law might also be concerned with the consequences of breaking it—having to pay a fine or to spend time in jail. Those who believe that Church teaching is always right and just seek to keep canon law as a way of being loyal to God. And yet, the Church is a human institution, and has been wrong in its teaching in a number of cases: agreeing to slavery, only recently speaking out about capital punishment, the judgment and rejection of LGBTQ men and women.

Those who believe that Church teaching is always right and just seek to keep canon law as a way of being loyal to God. And yet, the Church is a human institution, and has been wrong in its teaching in a number of cases: agreeing to slavery, only recently speaking out about capital punishment, the judgment and rejection of LGBTQ men and women. Then there is God’s law as it is revealed in the Gospels. Jesus taught us to love, only love. This includes feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, visiting the sick and those in prison, welcoming the stranger, burying the dead. He taught and modeled non-violence as stones were dropped and swords put away. He taught forgiveness, seventy times seven times. If these laws of the Gospel are not being followed, we are called to, and we simply must, exercise our moral authority: to speak out, to stand up, to shine a light into the night of injustice and immorality.

Then there is God’s law as it is revealed in the Gospels. Jesus taught us to love, only love. This includes feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, visiting the sick and those in prison, welcoming the stranger, burying the dead. He taught and modeled non-violence as stones were dropped and swords put away. He taught forgiveness, seventy times seven times. If these laws of the Gospel are not being followed, we are called to, and we simply must, exercise our moral authority: to speak out, to stand up, to shine a light into the night of injustice and immorality. We exercise moral authority in three ways: in educating others regarding the Gospel message; in doing direct service to those treated unjustly or who are in need; and in changing systems that sustain immoral treatment of our brothers and sisters, the dear neighbor. Living the “status quo,” to simply keep the peace, does not indeed keep peace, and is often irresponsible. To act on our moral authority, let us always and everywhere choose to follow God’s law of love, peace, and justice.

We exercise moral authority in three ways: in educating others regarding the Gospel message; in doing direct service to those treated unjustly or who are in need; and in changing systems that sustain immoral treatment of our brothers and sisters, the dear neighbor. Living the “status quo,” to simply keep the peace, does not indeed keep peace, and is often irresponsible. To act on our moral authority, let us always and everywhere choose to follow God’s law of love, peace, and justice.

After nine years at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, Sister Sallie Latkovich was elected to and currently serves on the Leadership Team of the Congregation of St. Joseph.

After nine years at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, Sister Sallie Latkovich was elected to and currently serves on the Leadership Team of the Congregation of St. Joseph.

Birds are back, filling the air with spring song, both the permanent residents, and the migrants who come only for the season, to procreate and raise their young before packing up and heading south again. Listening to their daily songs, I can’t help pondering how curious it is that they are unconcerned about, and oblivious to, the artificial borders and boundaries we draw on our maps. They are not stopped for border checks, put in detention centers, or required to prove their “right” to flock across every kind of “border” from south to north and back again. If only all humans had the freedom of birds.

Birds are back, filling the air with spring song, both the permanent residents, and the migrants who come only for the season, to procreate and raise their young before packing up and heading south again. Listening to their daily songs, I can’t help pondering how curious it is that they are unconcerned about, and oblivious to, the artificial borders and boundaries we draw on our maps. They are not stopped for border checks, put in detention centers, or required to prove their “right” to flock across every kind of “border” from south to north and back again. If only all humans had the freedom of birds. Sadly we don’t. Instead we label those who are seeking freedom, asylum, safety, and just a taste of the abundance we have, as illegal and unwelcome. We detain them (relieving them of shoelaces and belts), sometimes imprison them—we degrade their humanity in our attempt to ensure our own safety.

Sadly we don’t. Instead we label those who are seeking freedom, asylum, safety, and just a taste of the abundance we have, as illegal and unwelcome. We detain them (relieving them of shoelaces and belts), sometimes imprison them—we degrade their humanity in our attempt to ensure our own safety.

And this brings me back to my, now cooling, tea, and to our patron, Joseph—Joseph the worker. The loving parent, who provided safety for his son, both as an infant refugee, and throughout his youth in Nazareth. I have to believe that this is what all children of God deserve, and what we have to work for, as we celebrate resurrection and move toward growing in the gifts of the Spirit given at Pentecost. Safety, new life, renewal whatever the season or circumstances of our lives—I want to remember all of this as I celebrate and rejoice in this season.

And this brings me back to my, now cooling, tea, and to our patron, Joseph—Joseph the worker. The loving parent, who provided safety for his son, both as an infant refugee, and throughout his youth in Nazareth. I have to believe that this is what all children of God deserve, and what we have to work for, as we celebrate resurrection and move toward growing in the gifts of the Spirit given at Pentecost. Safety, new life, renewal whatever the season or circumstances of our lives—I want to remember all of this as I celebrate and rejoice in this season.

About the Author

About the Author